Researcher (geology):

Lilja Rún Bjarnadóttir

Cruise leader:

Børge Holte

Communication advisor:

Beate Hoddevik Sunnset

0047 908 21 630

Published: 15.06.2015 Updated: 23.06.2015

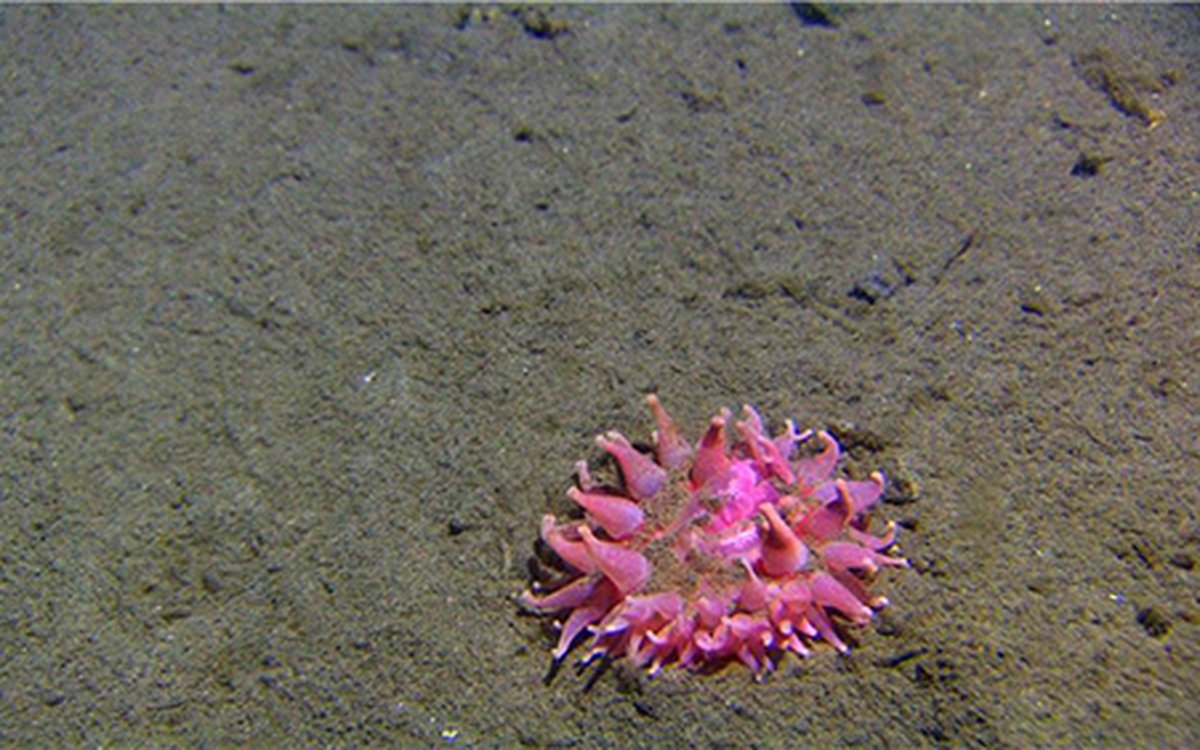

Overview map showing the location of the study area. The black arrow points to The Helmet, and the red polygon indicates MAREANOs 2015 sampling area in the Barents Sea. The peninsula Varangerhalvøya in northern Norway is marked in. TB: Tiddlybanken; TIB: Thor Iversenbanken.

How does a giant bump on the seabed like this form?

The explanation lies in the deeper layers of the continental shelf. Long ago, during Carboniferous-Permian times (350-250 mill. Years BP), piles of salt were deposited in a long-since evaporated sea. Over time the salt deposits rose slowly but steadily to the surface, as tenacious, pillar-shaped bodies known as salt diapirs. This upwards movement occured because salt has a lower density than the overlying sedimentary rocks, which makes it float slowly but steadily upwards through denser rocks. As it rose the salt lifted and deformed the rocks and sediment layers in its path, sometimes ripping out blocks from older deep layers and bringing them up to the surface of the seabed. In the surrounding area there are many salt diapirs that come close to the surface but none which actually protrude as clearly as The Helmet. (See also: Salt diapir and gas leakage on Tiddlybanken)

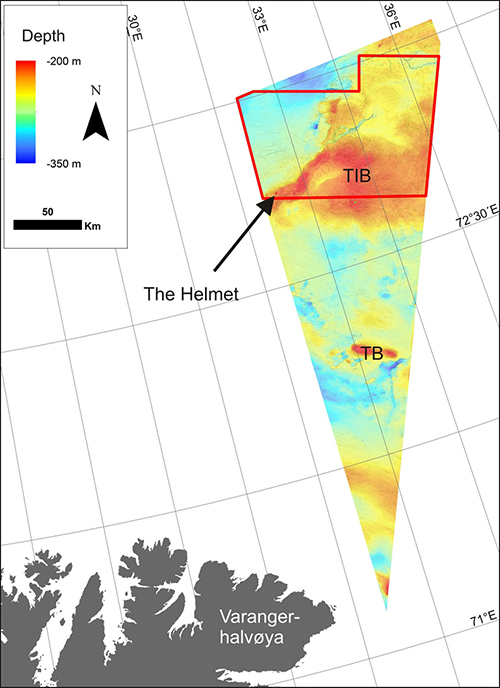

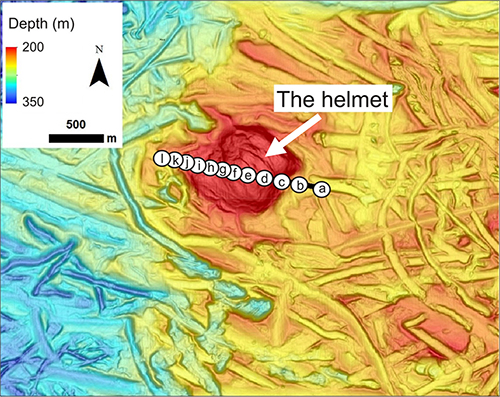

Shaded relief image of the seabed, based on a terrain model with 5 m resolution. The white arrow points to The Helmet, where the water depth is 165-210 metres. The furrows on the seabed are iceberg ploughmarks. The white circles marked a-l are located along the video transect and indicate the locations of pictures a-l below.

Filming the Helmet from east to west

We crossed The Helmet with the video rig, acquiring video data from a 1.4 km stretch of seabed over which large variations in bottom type were observed. At first, on the eastern side of The Helmet, there was not so much life to be seen but as we moved westwards and ascended the eastern slope of The Helmet, both the geology and biology got more exciting. The bottom type which started as mud became increasingly mixed with fine gravel then coarser gravel as we moved upwards, becoming dominated by cobbles and boulders by the time we reached the top of The Helmet. As we descended the western side of The Helmet the bottom type gradually became finer ending in mud again as we reached the flat seabed.

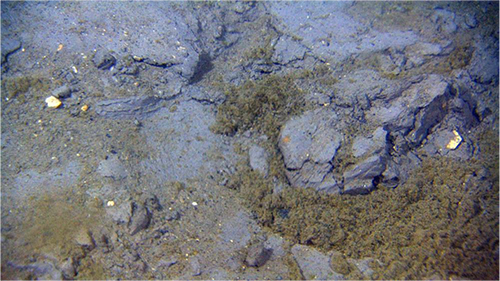

Picture a: Dense glacimarine clay with patches of fine gravel, sand and more brownish biogenic material (algae)

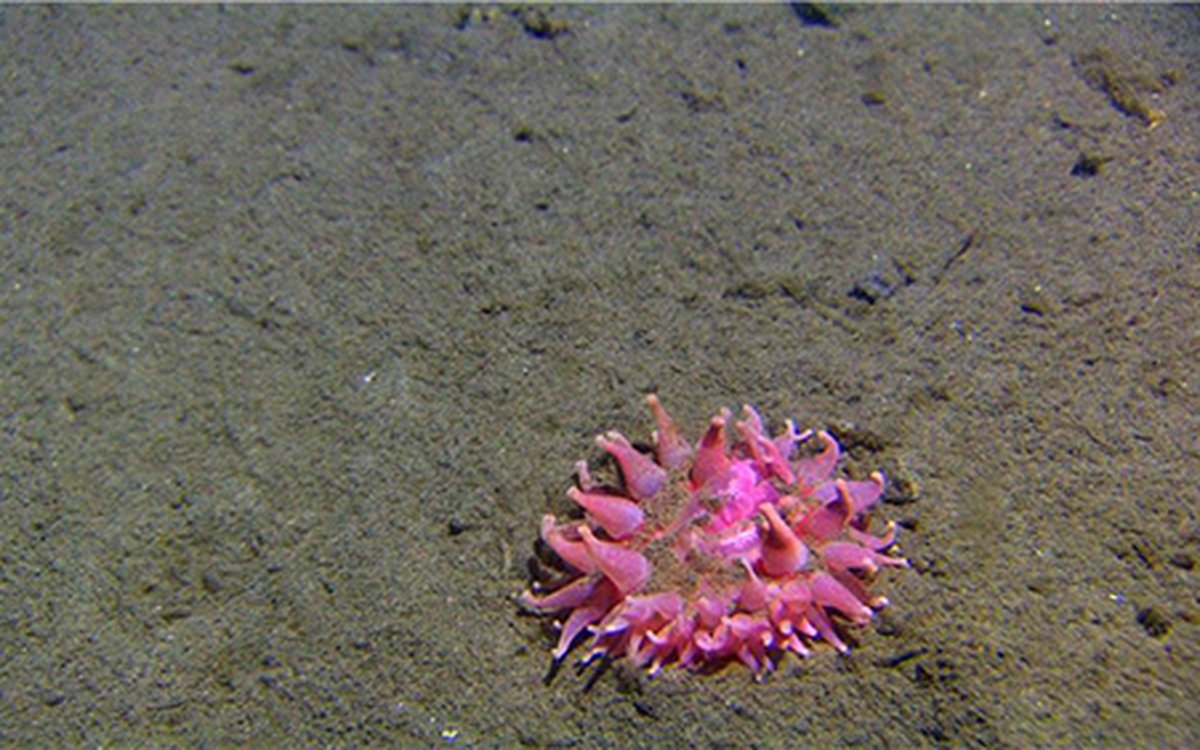

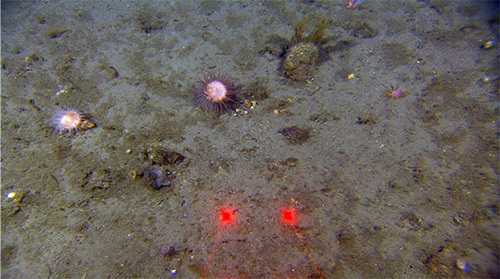

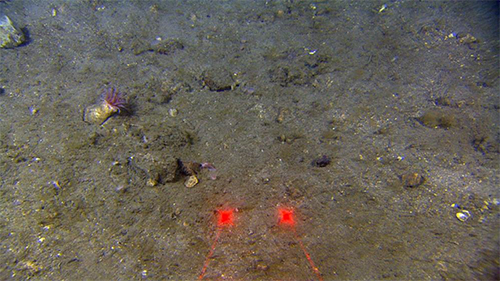

Picture b: At the foot of the eastern slope the bottom is characterised by sandy mud with a little gravel and small cobbles, providing a good place for pink anemones. The distance between the laser points is 10 cm.

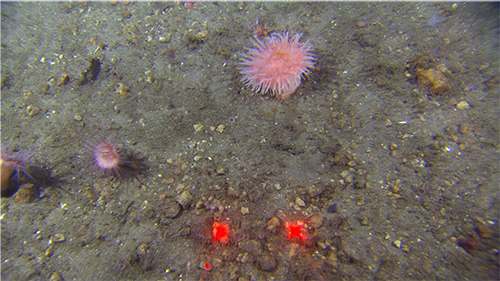

Picture c: As we move up the steep side of The Helmet the bottom becomes increasingly coarse. On the bottom we see that the sandy mud contains a good deal of gravel. This is a prime spot for the charismatic pink anemones.

Picture d: At the shallowest part of the transect we were interested to find so much light-coloured gravel, cobbles and boulders.

Picture e: Here and there cream-coloured bedrock shone out from the seabed – maybe this was the salt reaching the surface? Or perhaps these were examples of the Cretaceous rocks that dominate this part of the Barents Sea? We don’t have a definitive answer to that from just video observations and further investigation will be required.

Picture f: Cobbles and gravel neatly arranged on the seabed and adorned with pink anemones.

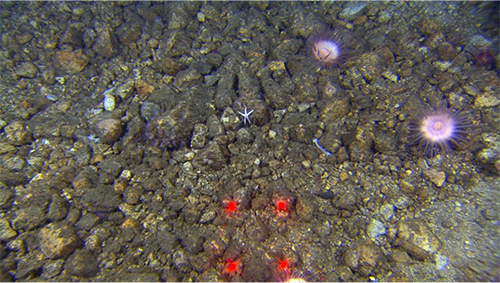

Picture g: Here bedrock is visible the seabed and heavily encrusted in biological matter. The bedrock in this area may consist of salt.

Picture h: As we start descending the western flank of The Helmet, the seabed is still dominated by coarse sediments, becoming finer as we move downslope.

Picture i: Gravel with anemones (Hormathidae).

Picture j: Sandy gravel. A Hormathidae anemone has settled on the hard bottom. These are common everywhere where there is something to hold onto, such as on rocks, gravel or even the shell of a hermit crab!

Picture k: Gravelly sandy mud close to the western end of the transect.

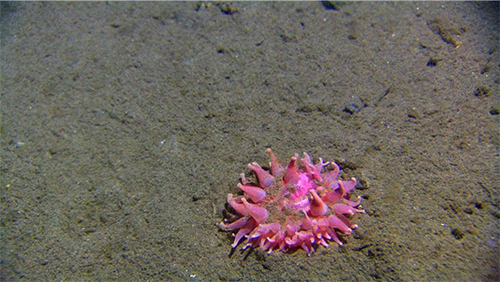

Picture l: We ended the transect on a soft muddy bottom with a lone and beautiful anemone.